We had a successful two weeks. We had a large group of 35 people in total and we visited several communities around Pinares, held daily clinics in Pinares, did a CHI in each of the surrounding towns and also checked up on water filters and stoves, tested water quality of filters and then cleaned and replaced broken filter parts. We also had an overnight hike to Llano de Balas that about 15 people participated in. The translators from La Ceiba were great!

University of Wyoming: Agua Salada June 30 – July 8

The University of Wyoming had a blast on the 2nd of their three yearly trips. They camped out, for the first time, in their newly finished Clinic in Agua Salada. The brigade came down in full force with 20 members ranging from Spanish majors and social workers to doctors, nurses and a dentist. In addition, one of the leaders was a midwife, and they had an engineer, Spanish teacher and a handyman fire fighter on board.

Over a span of 5 workdays they saw over 400 patients for medical consults, dentistry and via home visits including one in-home birth. In addition, the brigade worked hard teaching English classes, visiting schools, meeting with the local midwives and teaming with the community to plan the logistics of their new clinic. With all this work they still had enough energy to visit the local waterfalls and play soccer with the local kids. The community was sad to see them go and was so grateful that they decided to throw the brigade a dance party on the last night. The brigade was an over the top success and we are so excited to see them back in November! Thanks to all the members for their inspiring work and amazing enthusiastic attitude, we are eagerly awaiting your return!

Over a span of 5 workdays they saw over 400 patients for medical consults, dentistry and via home visits including one in-home birth. In addition, the brigade worked hard teaching English classes, visiting schools, meeting with the local midwives and teaming with the community to plan the logistics of their new clinic. With all this work they still had enough energy to visit the local waterfalls and play soccer with the local kids. The community was sad to see them go and was so grateful that they decided to throw the brigade a dance party on the last night. The brigade was an over the top success and we are so excited to see them back in November! Thanks to all the members for their inspiring work and amazing enthusiastic attitude, we are eagerly awaiting your return!

Dental Brigade: June 18th – June 27th

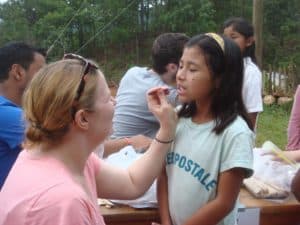

The Tepe’s dental brigade flew by with 4 work-filled workdays and a weekend full of meetings. Dr. Larry and Dr. Jan Tepe made their first of 2 visits this year bringing with them a dental surgeon and a father and daughter team of a dentist and his daughter who worked as both a translator and assistant. The days ranged from 20 – almost 50 patients in addition to visits to 5 different schools, meetings with three town mayors and Shoulder-to-Shoulder dentists at both clinic sites.

The Tepe’s dental brigade flew by with 4 work-filled workdays and a weekend full of meetings. Dr. Larry and Dr. Jan Tepe made their first of 2 visits this year bringing with them a dental surgeon and a father and daughter team of a dentist and his daughter who worked as both a translator and assistant. The days ranged from 20 – almost 50 patients in addition to visits to 5 different schools, meetings with three town mayors and Shoulder-to-Shoulder dentists at both clinic sites.

They spent their time in the Concepcion clinic working side by side with the head of the dentistry department, Dr. Idalia, seeing patients, doing minor surgeries and education the community about the importance of good dental hygiene.

Their dental education project that they have in 5 local schools received rave reviews after a quick visit and mouth check of all the students. Thanks to the hard work of the promoters, Shoulder-to-Shoulder dentists and schoolteachers, the Tepe’s were ecstatic and amazed at how clean kid’s teeth were.

In their absence over the next few months, their projects and contributions to the

dental programs will help to keep thousands of mouth healthy. Thanks to all for your hard work and dedication so such an important part of a healthy lifestyle!

dental programs will help to keep thousands of mouth healthy. Thanks to all for your hard work and dedication so such an important part of a healthy lifestyle!