Matt and the MAHEC Brigade

| MAHEC by Backpack Matt |

The first brigade I worked with as a Shoulder to Shoulder brigade coordinator was MAHEC. They arrived on February 10th and stayed until the 22nd. It was a group of ten people comprised of five doctors, a pharmacist, a pharmacy student, a medical student, a psychiatrist, and the son of one of the doctors. MAHEC stands for Mountain Area Health Education Center and is located in North Carolina. We had a filled itinerary for their stay here, and I spent a lot of time not only organizing and coordinating activities but also confirming and reconfirming them. I think my past experience organizing camps in Malaysia had prepared me well for these tasks. I was used to having people ignore phone calls, agree to something only to forget later, and read messages and not respond. It was challenging, but at the same rewarding to be able to overcome those obstacles and have what I thought was a great brigade.

After about five hours crammed into a bus from the airport, we arrived in La Esperanza where we spent the first night. The following morning I gave a short walking tour of the city and we visited La Gruta which is a religious site that overlooks the city, the public baths (which are a lot nicer than they sound), and the favorite gringo coffee shop La Fuente. Afterwards, we piled back into the bus and made our way to Camasca where they would spend the duration of their time. They were set up in the basement of the Evangelical church, where there were three rooms with bunk beds and a larger common area with tables. Working with us throughout the brigade were Eduardo, a translator, Alan who is Gustavo’s son (Gustavo is the other coordinator), Yeni (pronounced Jenny), and Nila. Yeni was our chef for the week and her experience cooking in restaurants in the U.S. paid off. We ate like kings. Nila assisted Yeni in the kitchen, which normally meant making the tortillas, as well as other general cleaning. They were a fantastic team with whom I spoke and listened to a lot of Spanish.

We followed the same schedule for all of the weekdays. Breakfast would be ready by seven, and by eight we were off to one of two locations. Every day two doctors would be assigned to stay in the health center in Camasca and assist the doctors there with seeing patients. I accompanied them most days as a translator, so that I could be in town for other meetings and because I didn’t trust myself to drive a manual truck. The rest of the brigade would head out into a different community each day to perform house visits. Camasca is an area that is made up of several aldeas (small villages) and the poor quality of roads, coupled with the lack of transportation, makes it difficult for some folks to come into the center of town to receive medical treatment. The psychiatrist, on the other hand, had a slightly different schedule. He wanted to try to reach out to people in town to come talk to him about their problems, something that has rarely, if ever, been offered to the people of Camasca. To get the word out Dr. Tom and I visited the local radio station. We announced his presence in the clinic and talked about a few of the stigmas about mental health. A great resource during this process was Profe Edwin, who spoke more bluntly on the radio. He acknowledged that there was abuse, alcoholism, and drug addiction within the community and here was someone who wanted to help. Although the talk we attempted to organize fell through when the power went out, Dr. Tom was still able to spend two days in the high school working with students in a one on one setting. He told me that there were some powerful stories and he felt inspired to return in August with the next MAHEC brigade with more psychiatrists and to try to set up a more lasting type of support system.

In addition to administering medical care, the brigade had a lot of fun in the community. There were afternoon soccer games on the smaller indoor court with kids in town. Many folks enjoyed walking up to the top of the mountain for the valley views below. Profe Iris had us up for juice and watermelon one evening. We visited the rocks of the sun for a stunning sunset. Dr. Tom and I were invited back on the radio later in the week where we assisted Profe Edwin with a raffle. Dr. Tom would draw the name, announce the number, and hand me the paper. My job was to decipher the name and hometown, and then give a short thanks for participating! Or good luck next time! A few people from home were able to find the link and listen to me obnoxiously rolling my R’s and getting very into the character of radio station host. The most entertaining activity of the week was our trip on Saturday to a waterfall about one hour away. We rented a minibus for the day, packed lunches that Yeni prepared for us, and drove to Colomancagua. The waterfall was part of the river that divides Honduras and El Salvador. Due to the small number of Hondurans that can swim, we had the place all to ourselves. It was a relaxing day off and one of the memorable places I’ve been to in Honduras.

The last day in Camasca was eventful, to say the least. After organizing a farewell dinner for the brigade with all of the Hondurans who had assisted us, I was informed by Dr. Rolyn, who works in the clinic, that it was not sufficient. He said there needed to be a ceremony at the bilingual school. Early the next morning, with the help of the teachers at the bilingual school, we scrambled to put together a small presentation. There was the national anthem, traditional dancing, and handmade thank you cards. We also gave the kids a short talk about washing hands, brushing teeth, and avoiding junk food. Although I’m not a fan of taking the kids away from their learning to appease foreigners, I do think everyone enjoyed themselves. The other big part of the last day in Camasca was a talk at the high school. I had spoken with Profe Edwin ahead of time and he gave me a list of topics to discuss that included values, motivation, drugs and alcohol, sexuality and hygiene. The brigade strategized the night before and came up with some superb ideas to get the kids involved and talking. They handed out statistics written in Spanish on small notecards to the kids, and as a class, we decided if they were true or false. Then we had them write anonymous questions that we answered. I was shocked at the lack of knowledge in some cases. I realized that there aren’t many resources available about these issues, but not having these discussions creates a dangerous gap of information that contributes to things like teenage pregnancy and alcohol and drug use. We made it clear that we were not there to tell kids what to do, but to provide them with as much information as possible so that they can make informed decisions, and know all of the risks associated with them. I do think the students benefited a lot from the talks, just as I know my cheeks were bright red the entire time as I did some of the more sensitive translations.

And just like that, it was time for the brigade to head home. I want to thank Dr. Amy, Dr. Brittney, Dr. Brian, Dr. Kyle, Dr. Rebecca, Irene, Kaitlyn, Caleb, Dr. Tom, and Braxton for their hard work and service to the people of Camasca. We anxiously await their return.

MBT

Shoulder to Shoulder Connects Rural Honduran Communities to KA Lite

Written by Grace Twohig

Grace is a long-term volunteer working with Shoulder to Shoulder’s CREE (Centro Regional para Excelencia en Educación or Regional Center for Excellence in Education) program. She has been amazing at extending our impact in assisting local schools. This blog was also published on the learningequaily.org website blog.

Shoulder to Shoulder’s education mission, CREE, focuses on bringing high quality education to rural areas where access is extremely limited. KA Lite has been one of our main methods in connecting these disconnected communities to better STEM education. To paint a picture, we are working in Southern Intibucá with a total population of about 70, 000. It is one of the poorest of the 18 “departments” (states) of Honduras. Shoulder to Shoulder has been working here for over 25 years.

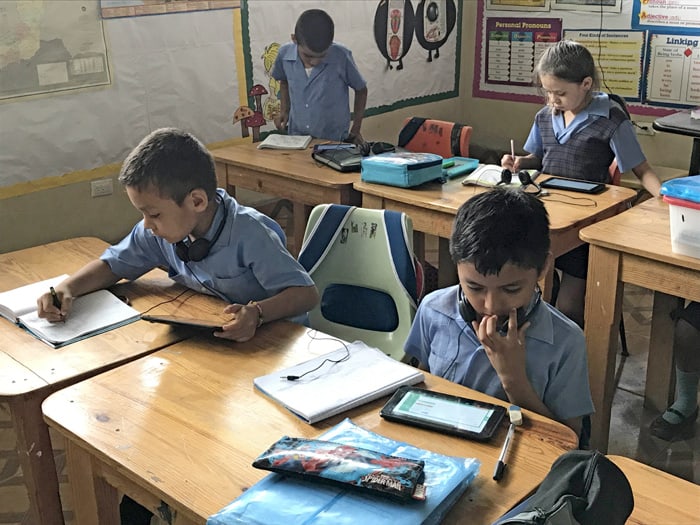

Currently, we have KA Lite deployed in three high schools and two grade schools, within three towns. There we have deployed a total of 7 servers and 230 tablets. In the high schools, we are covering math and science classes for the whole school. We are currently touching over 1,000 children, but teachers are still learning how to best use it. Slowly but surely, as our network is growing, word is spreading of this new method of learning and teaching. We have contacts and interest in many other towns and our expansion is ongoing. Our goal is to deploy KA Lite throughout all Intibucá over time, to about 15,000 students.

Paul Carey (a StoS volunteer) and I are meeting with prospective educational leaders in neighboring towns. We leave each meeting so encouraged. We are working in a country where things move slowly – “Honduran Time” as we say – and many times promises to the poor never materialize. But those bus rides back from each town are filled with excited conversations, hope, and respect for the leaders that are so committed to bettering the education for their community. In the end, we are learning that taking our time and having patience is well worth it. Our mission is not to “give” and “bring” but to “train” and “form partners.” KA Lite is something to be integrated into the schools and for them to take ownership of – we are just here to light the fire a little.

Our last meeting was in a town called Santa Lucia where we met Luis Pineda – the educational coordinator for his district. After installing and then training the professors at the high school on KA Lite, Luis came to us with a humbling request. Each town has various “aldeas” or villages that pertain to it in the surrounding mountainside. Luis has a big heart for the villages, as he worked most of his life in one in a grade school. He was one of three teachers, collectively teaching grades 1-6…a very typical situation. Whereas I see a huge lack of access to resources in the towns I’m going to, he attempted to paint a picture of how much worse it was for the villages, without any cell service or power much of the time. Their resources are much scarcer. Above all, he wanted us to know that he doesn’t want them to remain forgotten. His request was that we try to bring KA Lite, the bare minimum we are able to, even if it just a server, to these communities as well.

Luis has the type of ideas and heart that will propel us forward. The best ideas come from the people themselves, right? We have been so focused on getting into the main schools in towns – and we still will, but we want to shoot for the stars and see every child here in Intibucá with access to a better education. Only in the last five years or so have we started to turn our focus on education as well. Education is opportunity, opportunity is hope, and hope is something that children here in Honduras are so desperate for.

Using the KA Lite technology has given us a visible manifestation of the hope these students possess within themselves to succeed. In the high school in Camasca, Intibucá, the math teacher Daniel tells us about his students literally running to his class to get their tablets. One boy broke a chair mid-run a few weeks back and now unfortunately has a fine to pay. In the Magdalena high school, the teachers set benchmark goals for the amount of points earned in KA Lite by each student per quarter. There are a few kids that have more than tripled the point requirement by coming into school early or staying after class to work ahead. Extra time at school is a huge sacrifice to many of these kids as their walks home can be hours in the mountain – yet to them it is worth it.

I will never get tired of watching kids light up when it’s “KA Lite time” or training eager teachers how to use this technology in their classrooms.