Jens sits at our dining room table, our only table, in La Esperanza, as Laura and I explain to him the particular water challenges we face here in Intibucá. Jens, a 17 year old, US born citizen of German heritage, living in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, is visiting with us over the next few days. His older brother Jan, Jan’s friend Aeden, and Mario, a friend of both families and the driver/chaperon for the trip, are all visiting us in our small and modest home. Aeden is home from college in Prague where he studies cinematography. Jan is interested in the same career, but studies at Emory University in Georgia. Shoulder to Shoulder has contracted with Aeden to produce three videos: two will be short ones on brigades and Shoulder to Shoulder in general, and the third will be a documentary on the bilingual school. Presently, we’re trying to arrange a fold out coach and three mattresses on our limited floor space so everyone can sleep. Jens continues to incredulously question us on the water, unwilling to conceive that water runs only every other day. “But, what do you do about that ‘take a shower every day’ rule?” We then introduce Jens to the concept of a bucket shower, a concept he’ll become familiar with over the next three days.

The rural, isolated, poor, frontier region of Intibucá is very unfamiliar to our four guests from Tegucigalpa. You might say that it presents as more foreign to them than it would have even to us when we first arrived. But they have all come with a spirit of openness, acceptance, and generosity. They capture on video the commitment to service in Pinares where Virginia Commonwealth University and Fairfax Family Practice Centers are holding their two week medical brigade. After a morning and afternoon of videotaping there, we drive south toward Concepcion where our guests will stay with us in our home there. It is clear that Mario doesn’t believe me when I tell him that three minutes after leaving Pinares we’ll run out of pavement. When we begin bumping up and down, navigating the trenches where rain has eroded the road, he asks how far to Concepcion. “Maybe ten miles, but it will take us about an hour.” Mario works with the Central American Bank. The Central American Bank subsidized the paving of this road. According to their records, it’s been paved all the way to Camasca. He will register an official complaint report. But our going is slow, not only because of the road, but also because every five minutes or so, Aeden and Jan yell to stop the car. They grab their equipment and jump out of the car. They take beautiful shots of the expansive terrain, the majestic mountains, and the awe it inspires. I take this road too often. I no longer recognize the breathtaking views or the bumpy drive.

In Concepcion we all settle into our home. There is a lot more space and rooms, but we’re short a mattress. Mario disappears for a short time, and, unbeknownst to us, borrows a mattress from our neighbors. We tell the boys there is always water at night, but we often lose it for a few hours in the morning. They take no heed to our warning. In the morning, as they take their bucket showers, Laura and I are holding back our laughter as we watch them throwing cold water from our pila onto their bodies. So energetic and enthusiastic, so bright and ready to take on the world. With the medium of video, they will make art, their free expression to inspire.

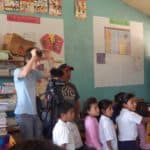

We head to Camasca and the bilingual school. Here, they are recording a view of hope. The parents send their children to our school with a great hope of something new, of achievement, of a better day. I can’t help think about those expansive, limitless views of the mountains from yesterday. Ironic, here where boundless beauty is so easily witnessed in nature, the constraints of poverty are so clear. Poverty limits experience, limits the horizon. Aeden films Juan Carlos and Keilyn, two cousins who live two-hundred meters below the town proper. They don’t have much, but they do have a climb up a great hill every morning. It’s a rugged climb and I feel some shame for my self pity that the road I travel is not paved. The path Juan Carlos and Keilyn take is one with carved footholds into a slate, rock face. They climb, we climb, we film, we record, and this is hope. It springs upon us when we reach the summit, an opening appears. Then we’re at the school.

Some of us have been given much, some of us, little. But all of us have rutted roads to travel, and all of us can gaze upon the expansive beauty of our world. Can not all of us then pattern hope? We can remember and record. We can share. It is not so important from where we start our journeys, but the integrity of the journey is the clear testament of hope.